This has been a fruitful summer field season for monitoring. Early in the Spring, we finalized the 2-3-2 Multiparty Monitoring Plan and then put the plan to use! Field crews from Mountains Studies Institute and the Forest Stewards Guild were active in all four of the National Forests in the Rio Chama CFLRP landscape, the Rio Grande, Carson, Santa Fe, and San Juan National Forests.

We’ve spoken about the nuance of monitoring in a blog in the past, mentioning how it is iterative, adaptive, and acknowledges what it can and can’t do. Here, though, we want to highlight the beginning stages of this process and the successes thus far. Nothing is more emblematic than the collection of wild bees though I’ll do my best not to focus solely on bees. After all, we had plenty of people doing work, not just the bees

We’ve spoken about the nuance of monitoring in a blog in the past, mentioning how it is iterative, adaptive, and acknowledges what it can and can’t do. Here, though, we want to highlight the beginning stages of this process and the successes thus far. Nothing is more emblematic than the collection of wild bees though I’ll do my best not to focus solely on bees. After all, we had plenty of people doing work, not just the bees.

While the bees themselves are inherently charismatic just being themselves, what can they tell us about the landscape? Why do we monitor bees? It has to be more than some idle curiosity that ends up in our fridge.

Broadly, bees react and respond quickly to changes in their habitats. Their lifestyles and jobs as essential pollinators of native plants are closely tied to local areas, meaning that they indicate how landscapes are changing beyond just the macroscopic scale of how things look, showing us instead how they function. Often bees are overlooked for this, relegated to cute denizens, yet bee community health is a vital component of forest resilience. Pollinators and pollination is a foundational aspect of many ecosystems, keeping plants and trees alive, connecting them across spaces, and building diversity of species which increases the resilience to major disturbances.

A goal of the 2-3-2 is to work across boundaries. Bee monitoring is something the Bureau of Land Management has done in northern New Mexico and this work from the 2-3-2 can now expand that approach, tapping into existing data, telling the story of bees across large continuous regions and across different land owners and managers. Frankly, the bees do a great job of crossing boundaries.

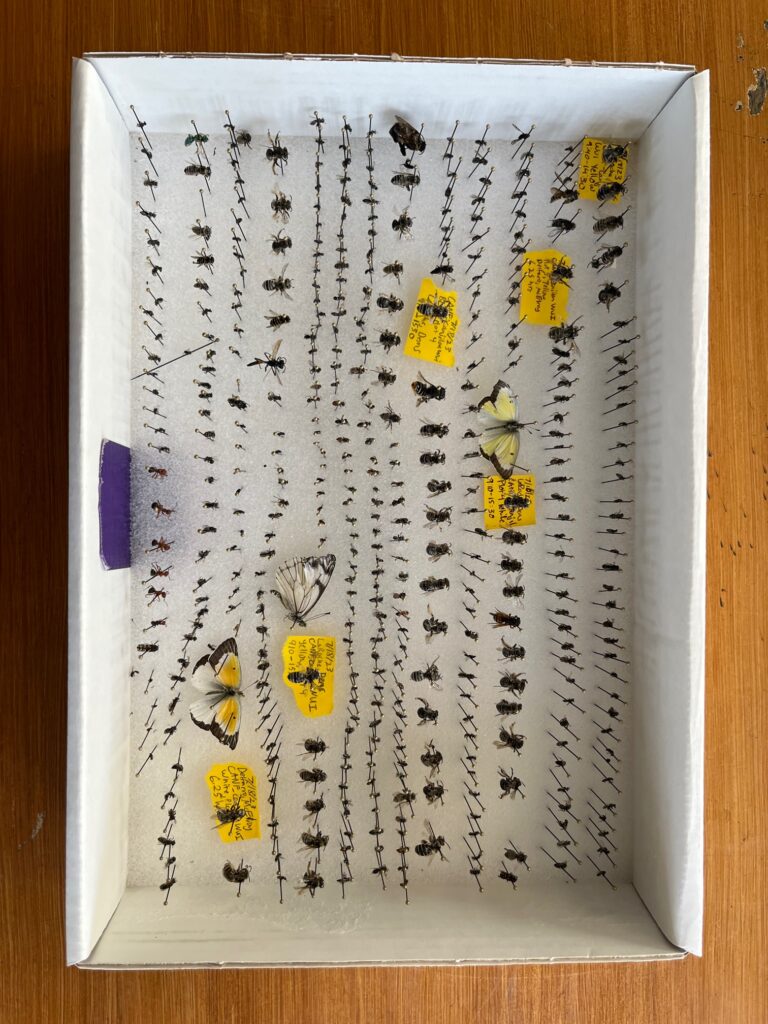

Dr. Olivia Carril, world renowned bee specialist and author of The Bees In Your Backyard, has helped us from the beginning to establish a bee monitoring protocol and now, to identify and analyze the bees that were collected over the summer.

But let’s get into the details on what exactly we look at when we monitor bees. It’s all about the health and diversity of bee communities — how are they doing and how many different ones are there. This brings up a pretty basic, yet important question: why is biodiversity good? It shows both a more resilient bee community and a more diverse and resilient plant community. As an article on Nature describes, “Biologically diverse communities are also more likely to contain species that confer resilience to that ecosystem because as a community accumulates species, there is a higher chance of any one of them having traits that enable them to adapt to a changing environment.”

When it comes to the connection between forest management and bee communities, not all disturbances affect bees equally, and promoting a mosaic of forest treatments and mixed-severity fire effects maximizes bee biodiversity and function at a landscape scale. For now, we’re understanding the current life of bees, but as forest management treatments and work sweep across the landscape, those bees’ lives will assuredly change, and we want to know how.

And before you think that we’re only looking at bees, we’re gathering baseline information on a whole host of ecological and socio-economic factors that I will lean into in future newsletters and blogs. Know thy land and know thy people. Our dedication to adaptive management requires that baseline understanding before we can compare and make actions.

Bees are not the only indicator of what’s happening on the landscape — they paint part of the picture, one that we hope to paint as fully and accurately as possible. As we transition from the field season, we’re committed to adaptive monitoring and will carve out time during the next 2-3-2 full partnership meeting to discuss, improve, and analyze what we’ve done so far. Additionally, socio-economic monitoring is ramping up this October.