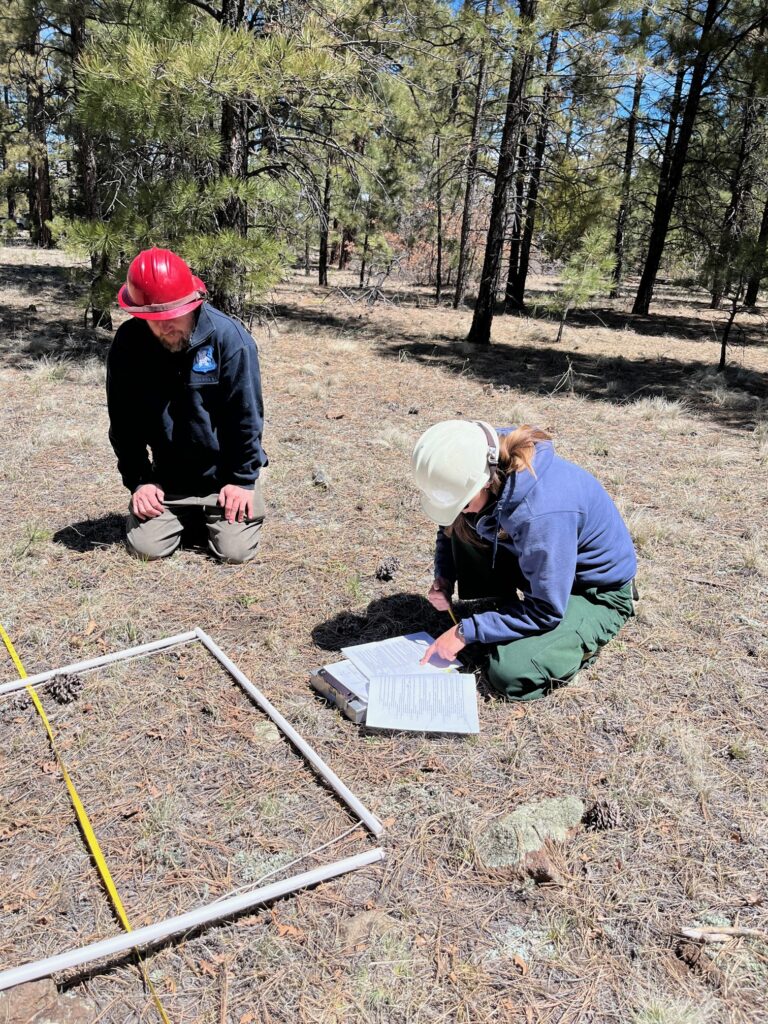

The 2-3-2 Partnership just finished the first edition of the Multiparty Monitoring Plan thanks to the dedicated hard work and collaboration of partners and staff. In fact, since it rolled out, the first on the ground monitoring took place in Tres Piedras.

All of it got me thinking. Why do we humans pay attention to things? Why do we pay attention at all? Do we decide to? Or do things draw our attention?

Are we powerless in our attention giving? I’d like to think not, for better and for worse.

Though some folks feel helplessly drawn to aspects of our world — a famous example being Marcel Proust and his poetic obsession with madeleines and nostalgia — most of us appear to decide to observe things, enjoy our time with certain spaces and activities, and feel compelled to follow our values. We make choices, and those choices produce outcomes that are not independent of our choosing.

The thing is, what we decide to pay attention to becomes more important to us because we’re paying attention. And that has real world consequences and can influence our behavior. For example, it may not seem like a radical act to focus energy on carbon capture technology — to read about, care for, and even fall in love with carbon capture — but that attention makes it more valuable to us and gives it more primacy. The result is a world where we dump enormous resources into a technology that may not have the answers we’re looking for and doesn’t push us to even question the nature of the question we’re asking. Maybe we should ask why we use so much energy. Or if we’re even tackling humanity’s greatest challenges if we only focus on CO2. Maybe we should ask how we can change as opposed to how a machine can change things for us.

Now let’s bring this to the idea of monitoring. How does it direct our actions? Our beliefs? Our future? Monitoring is not just an unbiased look, but an integral part of landscape management and collaborative processes. Our monitoring and observations, however objective in theory, can and will have implications on the wider world. If we don’t measure something, or don’t have the capacity to measure it (something like trust, let’s say), our actions can implicitly damage or destroy it. And those aspects of our work that are the hardest to measure may be the most telling!

Monitoring is an approximation. It is an attempt to know the whole by measuring some of the parts. That is not a knock on monitoring — it is important to have a sense of things and where they stand and use that information to bring people together, have conversations, and translate the numbers into stories and decisions — but it cannot be the final word in decision-making, and it fundamentally cannot include everything.

Monitoring depends on quantitative metrics. But once again, not everything is quantifiable, which can create unexpected and counterintuitive results.

Donella Meadows, a preeminent systems thinker, states in her book, Thinking in Systems: A Primer:

“If quantity is the center of our attention and language and institutions, if we motivate ourselves, rate ourselves, and reward ourselves on our ability to produce quantity, then quantity will be the result.“

Quantity cannot be the only outcome we’re looking for, right? The world is frankly not composed of things whose relationships are entirely defined by numbers (much to the chagrin of mathematicians and physicists). There are other attributes in this world besides numbers that are worthy of our attention, such as beauty, value, trust, love, and even Proust’s madeleines. This is not to say that we shouldn’t also look at the things that are quantifiable.

I spoke with Cody Dems, the Southwest Project Coordinator at Forest Stewards Guild, who led the collaborative process to develop the 2-3-2’s Multiparty Monitoring plan. He was there for the first monitoring work done at Tres Piedras which aimed to collect data before any work occurred and test the monitoring plan’s procedures and protocols in action. I asked him to think about the space in a poetic way along with his monitoring duties.

“Everything was waking up,” he noticed. “There was this slow energy building, this beautiful ponderosa forest has been in the daily routine — a rut — and doesn’t expect the exciting rejuvenation that is to come.”

While that isn’t the type of monitoring that is required, it’s important pay attention to the spaces that we work in, to see them as whole, alive, dynamic and interconnected. Ultimately, when it comes to paying attention and monitoring, we will follow the sage advice of Donella Meadows, “Pay attention to what is important, not just what is quantifiable.”

This brings up some important questions when thinking about our monitoring plan:

- What do we really want to be doing? The change we intend to make and the interventions we intend to implement are to help forests, watersheds, and communities be more resilient to disturbances like fire, drought, and climate change. That’s huge. That’s ambitious and visionary.

- How do we know we’re doing it? This is the difficult part. Sometimes we don’t know. If what we want is for a forest to be more resilient, that’s not easily identified or seen. There are certainly aspects of resilience that we can approximate, sure, but knowing we’re moving in the right direction takes humility, learning and an understanding and appreciation of complexity.

- How long can we extend our time horizons? Ten years is an impressive amount of time for a fruit fly, but the change that we’re looking to make, and the way we’re hoping to know it’s happening takes a long time, perhaps longer than our lifetimes. Let us aim for the timeline that fits our desired change, not try to fit our desired change into a specific timeline.

The answers I’ve just provided for these questions are easily written yet arduously followed. Which brings us back to the aforementioned monitoring plan. The idea of this blog is not to imply that monitoring shouldn’t happen or that we should only be introspective about our existence. We are part of the world. We cannot avoid influencing our world, so let’s strive for a more positive influence. Let us strive for learning and improvement. Let our monitoring inspire our conversations and dialogue. And for now, let us strive to measure what we can while acknowledging what we can’t. Now that’s what I call a Multiparty Monitoring Plan.